Technodiversity, permacomputing and anticapitalism

This article is based on a talk we did at the Hackmeeting at Zaragoza in september 2025. You can download the slides here.

You may download a zine version here (for now, we only have it in spanish).

Objectives

The objectives of this article are:

- Help articulate a critical theoretical framework that can serve as a base for social movements: we perceive that there is a widespread loss of historical memory and a lack of deep understanding of the origin of our current problems, especially what ideologies have brought us here. We want to fight the hopelessness that there is no horizon beyond capitalism with a critical discourse that helps us feel that we can have control over the narrative of our reality.

- Unify critical perspectives against technocapitalism: we want to connect the different perspectives and analyses that have already been made in the same solid and coherent discourse.

- Radicalizing activism: we need to identify the roots of the problem in order to conceive radically anti-capitalist perspectives, rather than lose ourselves in reforms or try to take control of capitalist technology, when actually it is the technology that controls us. It is necessary to attack the extractivism and industrial production that supports the current technology, inseparable from digitality.

- Motivating you to keep deepening on these topics.

Technocapitalism

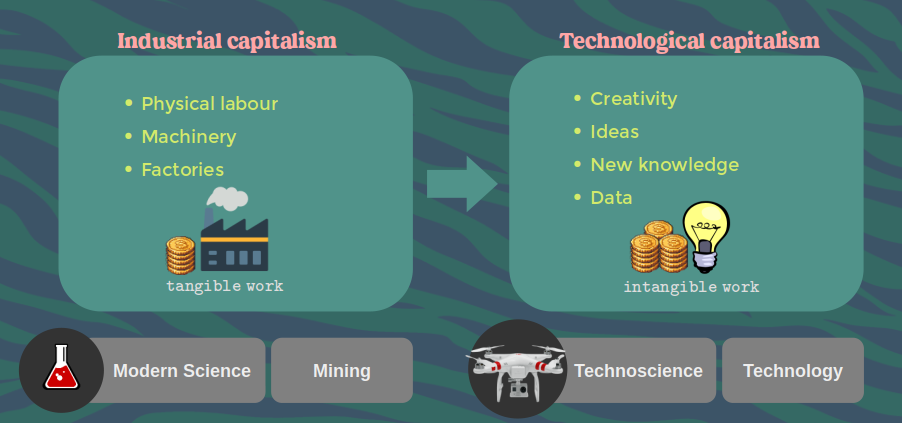

Technocapitalism, or technological capitalism, could be defined as an evolution of industrial capitalism, where instead of focusing on extracting capital from factories, machinery and physical work, that is, from tangible work; it focuses on extracting capital from intangible work, exploiting creativity, ideas, new knowledge and data to produce new commodities.

Industrial capitalism was based on modern science and mining to develop itself, while today’s technological capitalism is held on technoscience and technology.

All these branches (modern science, mining, technoscience and technology) should not be understood as mere disciplines of knowledge, but as the ideological engines of capitalism. Those are not objective or neutral fields.

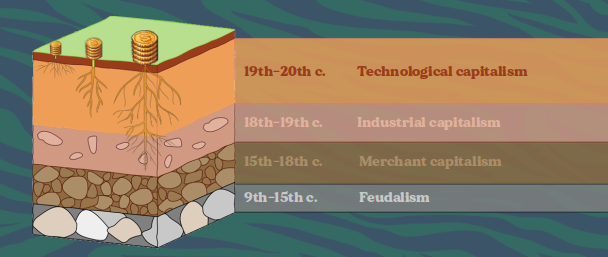

Layers of capitalism

Technocapitalism is the evolution of capitalism, changing its appearance to find new ways to accumulate capital, expanding its exploitation horizons. However, its previous versions do not disappear, but serve as a material and ideological base for the capitalist gears to keep it functioning.

This means that industrial capitalism has not disappeared, it has simply gone to the background and continues to live in the offshore factories, the mines, the exploitation of nature (includes humans as well), in serial production and all the production chains that this system needs.

Therefore, the ideology that sustains the current system has roots that extend to the oldest strata of past centuries, which leads us to the urgent need to deconstruct the complex ideological heritage that we have interiorized and that permeates our entire reality.

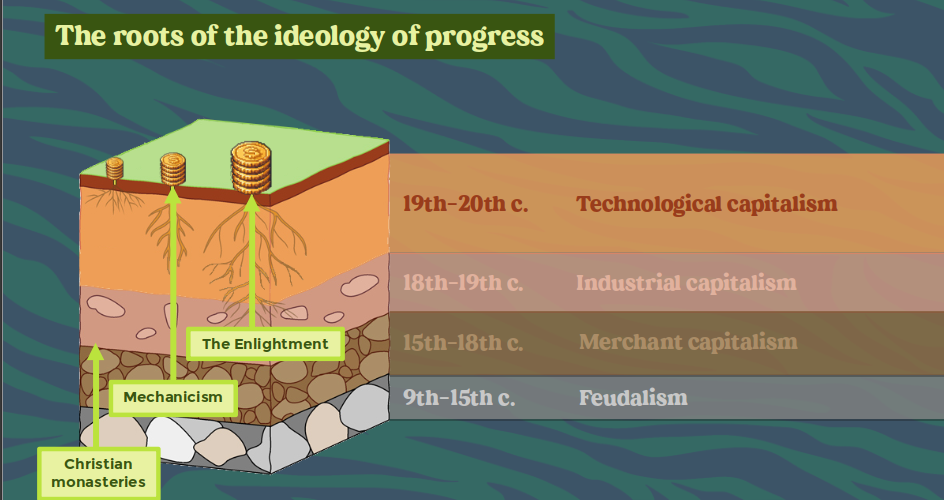

In the book Technique and Technology of Adrián Almazán, it identifies three processes in western culture that gave rise to the ideology of progress, and thus technological progress:

- The Christian Monasteries (9th century): were the first to introduce manual work as a way to achieve the perfection of the soul and its salvation, along with the prayer and reading of the Bible. This was a cultural transformation of the ancient world, laying the foundations for the emergence of a cult to work and the idea of progress.

- Mechanicism (16th century): mechanistic thought was a turn of vision over nature. So far, nature was understood as an organism that united self, society and cosmos. Nature was seen as a protective and generous mother who guaranteed everything necessary for life. However, at a time when mining was becoming a great source of economic benefits for the capitalists, this imaginary - the one that understood nature as an organism - acted as a moral limit that was an obstacle to the technical development needed for the exploitation of the land. In the face of this, a mechanistic thought started being promoted which:

- Morally justified the domination of nature by describing it as a machine, inert, objectified and predictable, which we can (and must) dominate through modern science.

- It represented a radical transformation in the way nature was understood, establishing the ideological shift from technique to technology.

- It is the foundation upon which modern science, technoscience, and technology are developed.

- The Enlightenment (18th century): at this point, the idea of progress ceased to be an ideal held by a few isolated individuals and became the ideology of the European dominant classes.

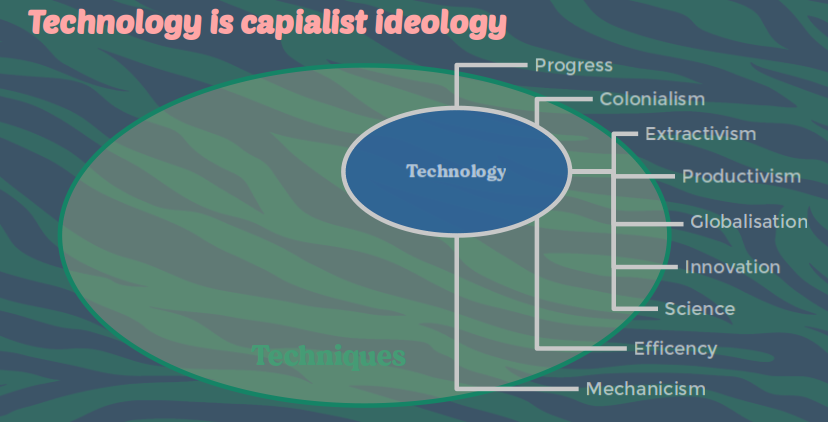

Technique versus technology

Before continuing to talk about technology, it is necessary to delve a little deeper into what technology is and how it relates to capitalism.

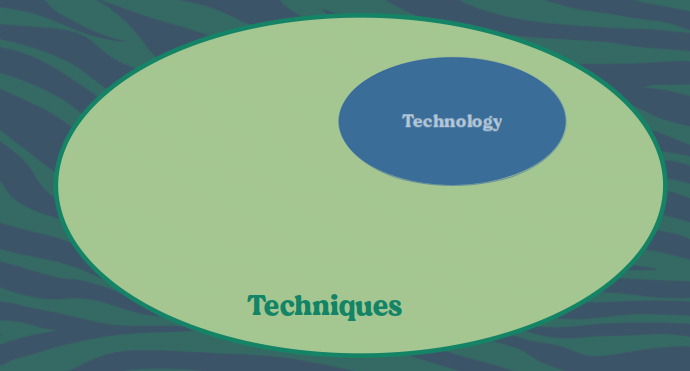

The book Technique and Technology provides a very coherent perspective: it understands that technology is inseparable from the ideology of capitalism and defines technology as a specific set of techniques developed from modern capitalism and industrialisation.

In other words, techniques are an attribute shared by all human societies and non-human species, while technology is a historical creation with an enormous ideological burden (progress, colonialism, extractivism, productivism, etc.).

Therefore, technology is not neutral; it is the culmination of an ideology that gained momentum in the 17th century, crystallising later in the 19th century, and which:

- Seeks to dominate, control and exploit nature but, above all, it seeks to justify it morally. The mechanistic school of thought of the 16th century defended mining exploitation with arguments such as: ‘Giving up metals (mining) condemned his contemporaries to return to feeding on roots and fruits and digging holes with their own hands in which to take refuge at night.’ (book ‘De Re Metallica by Agricola’, 1556).

This type of argument can still be heard today in response to criticism of technology or progress.

- Puts science at the service of technology. This total domination and conquest of nature can only be achieved by using the knowledge that science offered (and offers), already problematic in many aspects, but it went from seeking knowledge and new arguments as an end in itself, to creating new techniques that would allow human domination to expand. Thus placing itself at the service of technology (technoscience).

- Relates technological progress = social / moral progress.

Technology can’t be neutral because no technique is neutral. We will dig more into this later with the concept of technodiversity.

Therefore, we see a radical component in talking about techniques, as opposed to technologies, in order to discuss them from a post-capitalist perspective.

In this article, when we talk about technology, we are implicitly referring to capitalist technology.

Characteristics of technocapitalism

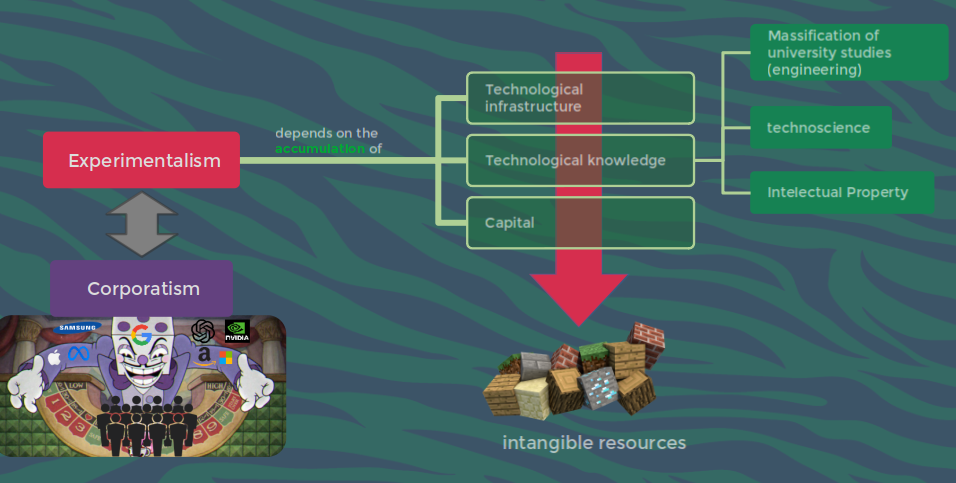

Experimentalism

Experimentalism, as defined in Luis Suarez-Villa’s book ‘Technocapitalism’, is technological and scientific research in the service of commercial interests. It means experimenting to obtain profits and power by any means, rather than experimenting for the sake of knowledge itself.

Experimentalism transcends the laboratory space that emerged with the experimental sciences of the last century and, instead of a laboratory in a room or enclosed space, experimentalism turns society as a whole into the great laboratory of technocapitalism. It is a laboratory with which the entire society is forced to interact and which, in turn, converts us into its test subjects.

We could understand this laboratory as what the factory system was to industrial capitalism. In this case, the most valuable resources of experimentalism are intangible resources, such as creativity, ideas, and data, which, due to their immateriality, are inherently social resources.

“This social dimension has turned experimentalism into a social phenomenon, co-opting institutions, destroying others, creating new ones, and encompassing all aspects of our lives.” - Technocapitalism: a critical prerspective on technological innovation and corporatism, Luis Suarez-Villa

One characteristic of experimentalism is its ability to redefine the reality of society as a whole through globalisation in a way that has never been seen before. Defining reality means that technocapitalism sets the agenda for the whole of society and its effects filter into our everyday reality, such as our dependence on electronic devices for everything, but also into our routine, politics, education, how we communicate, our desires, aspirations, needs…

It is interesting to consider that hundreds of years ago, scientific or technological ‘advances’ did not really change the lives of most people. This is because society and people’s daily lives were not linked to science or technology. Today, our reality is extremely linked to technology, along with an extreme dependence on it, so any technological change is a potential factor for social destabilisation.

In the digital sphere, we could understand that one of these factory-laboratories that exploit intangible resources would be the digital platforms (social networks, entertainment applications, video games, streaming platforms, online shopping, etc). Companies’ interest in these platforms stems from their great capacity for social experimentation, allowing them to modify and control users’ behaviour in order to alienate us with their capitalist interests.

In this dynamic of the virtualised factory-laboratory, we work 24 hours a day producing data. Information and creativity become commodities in the form of content and, at the same time, we become its consumers, while companies extract immense profits from this intangible work.

This system needs to create new means of extracting intangible resources, which are then converted into commodities to sell or used to continue extracting data. In the digital realm, some of these means could be:

- Commercial social networks (or best described as social traps)

- Open Source (which is not the same as Free Software)

- “Artificial Intelligence” or chatbots

On the other hand, we previously discussed the capacity of experimentalism to redefine reality. This has been made possible through a new form of corporatism, where technology corporations meddle in society and wield almost absolut power over it.

It is not just the most well-known companies but the entire spectrum of technology companies: from pharmaceuticals, agriculture (seed patents, pesticides, GMOs, etc.), the textile industry, renewable energies, semiconductor and microchip manufacturers, biorobotics, nanotechnology, bioinformatics, etc.

Experimentalism acts as the driving force behind technocapitalism, creating new structures with new modes of corporate organisation, new technologies, and new systems of accumulation designed to exploit intangible resources.

Technocapitalism has only been able to develop on the foundations laid by various processes of accumulation that enable the effective exploitation of intangible resources. These processes of accumulation are:

- Technological infrastructure: it takes the form of the construction of large laboratory facilities for science and engineering and, on the other hand, globalised communications infrastructures such as the Internet and the Web. It also includes any educational infrastructure related to technology and science, as these are crucial for the accumulation of technological knowledge.

- Technological knowledge: this is only possible because of this accumulated infrastructure and the collaboration between universities and businesses. It is this knowledge that makes technological research through science possible, transforming modern science into today’s technoscience.

- Capital: technocapitalism has boosted capital accumulation by finding easier and faster ways than its previous versions.

Accumulation of technological knowledge

We believe it is necessary to delve a little deeper into this form of accumulation. It is directly related to:

- The massification of university studies (engineering): just over 50 years ago, there was a rapid massification of university studies, and access to universities became a right previously reserved for the upper classes. Public and private resources were devoted to public universities to open their doors to a wider range of the population, promising that this would ensure a better future for us. This process went hand in hand with costly science and engineering programmes and the expansion of technology campuses. This laid one of the foundations for the development of technocapitalism, ideologically alienating students from their interests and creating an intellectual workforce that would be (and is) the salaried hands that keep technocapitalism running.

- Technoscience: science at the service of technology and, therefore, at the service of technocapitalism. Technoscience is extremely dependent on technology and loves complexity. It is guided by profitability, functionality, applicability, effectiveness and usefulness, and its ultimate goal is to create a technoscientific environment that transforms the everyday reality of the individual, introducing new consumer products and, as we mentioned earlier, redefining the reality of society.

- Innovation is the essence of technoscience through which knowledge and creativity are commodified. The goal of innovation is to introduce a new product to the market, but this inevitably means rendering old ways or knowledge as ‘obsolete’, that is, knowledge that is not profitable (at the moment). The obsolete knowledge is erased or made inaccesible and our possibilities are reduced. It is constant change; it is instability.

- The privatisation of knowledge through intellectual property. We also include the dispossession of knowledge through automation of manual labour and thought processes.

Destroy in order to build

If we are aware of how deeply rooted capitalist ideology is in our lives and how we unconsciously reproduce its discourse when thinking about technology, we can understand the fundamental need to deconstruct these ideas before we can construct and imagine radically anti-capitalist perspectives.

Some of the questions we can ask ourselves in this process of deconstruction are:

- Questioning how we contribute to technocapitalism:

- Are we challenging its ideological foundations?

- Are we reproducing it in our dynamics?

- Are we validating its ideology in our discourse?

- Does suggesting that there are “good uses” and “bad uses” of a technology reinforce the idea that “technology is neutral”?

- Do we question industrialisation?

- Do we question globalisation? The global and inmediate communications?

- The constant disponibility of the “servers” that make Internet work?

- Detecting the ideology of progress in our discourse

- Have we questioned the assertion that technological progress = social progress?

- Do we think that not using capitalist technology would be a step backwards?

- Do we consider a technology that depends on extractivism to be advanced?

- Do we consider techniques that do not rely on an extractive system to be less advanced?

- Do we consider that there is a single global development? What would be the ultimate goal of that progress/development?

- Do we prioritise the interdependence between colonialism and the production of technology (and digitality) in our discourse, or do we omit it because it seems “inevitable”?

- Analyse whether our proposals increase technological dependency. Technocapitalism needs to make technology the intermediary between us and reality, and to do so, it conquers every space in our lives.

- Using their technology means being deprived of other ways of doing things, creating the need to depend on their infrastructure.

- Defend collective autonomy above all else from technology, we cannot destroy a system if we depend on it.

- We need techniques and knowledge that respect or promote our autonomy from the system, not technologies dependent on extractivism, colonialism, and capitalist accumulation.

Also, we need to:

- Try to imagine futures detached from the ideology of ’technological progress’

- Radical strategies for the short term and long term

- The ultimate goal is to destroy capitalism and its extractivist model.

- Living with contradictions rather than trying to justify them: currently, we need to use capitalist technologies (mobile phones, computers, cars, etc.) even if we want to fight them, as we are forced to live within this system. Attempting to resolve these contradictions by creating concepts such as ‘feminist digital infrastructure’ or thinking that, for example, the ‘fediverse is anti-capitalist’ obscures these contradictions and validates technocapitalism.

- Positioning the strategic uses we can make of capitalist technology within a long-term strategy (e.g. using the fediverse instead of commercial social networks is a strategic use of capitalist technology because we regain a little more autonomy)

- Do not fall into the idea ‘the end justifies the means’. Draw red lines on which technologies we refuse to use (e.g. ‘Artificial Intelligence’ increases dependency, extractivism and the dispossession of collective knowledge).

Perspectives for a radical movement

We have come across several perspectives that we find extremely valuable for finding the ideological cracks of capitalism, such as: technodiversity and permacomputing.

We will not cover here the Luddite Movement but it offers a lot of historical context and resistances against the expansion of industralisation which we find very valuable as well.

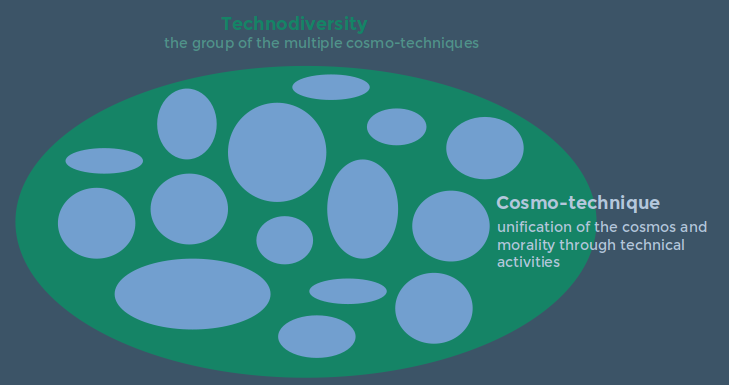

Technodiversity

We need our own concepts, distinct from the hegemonic ones, that allow us to confront the current discourse and help us evoke different ways of understanding and describing reality. For this reason, we find the following concepts to be valuable contributions to the struggle against technocapitalism.

Chinese writer Yuk Hui, graduate in philosophy and computer science, has reflected on the meaning of technique, developing the concepts of ‘cosmo-techniques’ and ‘technodiversity’ in several of his books.

Yuk Hui explains that techniques are the result of particular worldviews and go beyond their functionality or usefulness, so we should not talk about techniques but rather cosmotechnics.

Cosmo-techniques is the unification of the cosmos and morality through technical activities. In other words, techniques (or technology) are not ‘neutral’; they will always contain the culture and worldview of those who develop them.

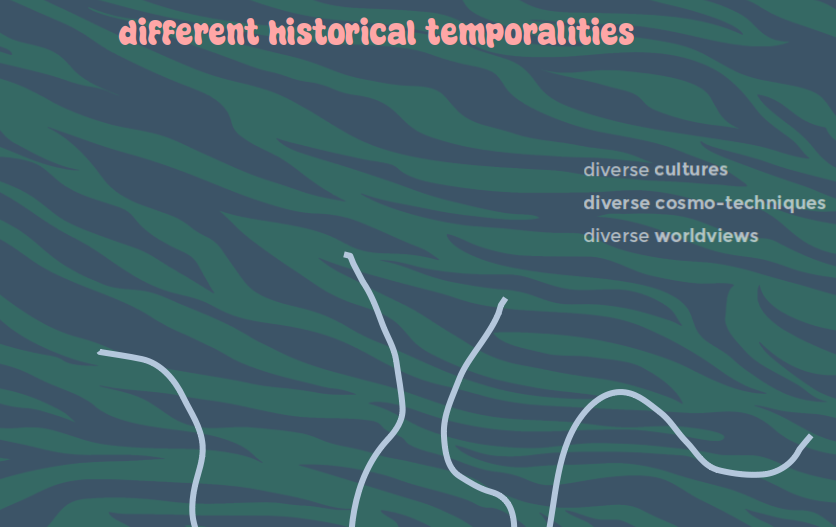

The multiplicity of cosmo-techniques make up technodiversity.

This broader way of understanding techniques, which frames every technique within a worldview, shows that it is the beliefs or worldview of a culture that act as the limit for technique development, that is, it delimits what is technically possible and what is not.

For example, the capitalist worldview did not serve as a brake on the development of the atomic bomb, a highly destructive technology, due to its lack of limits and it was possible because its ideology justifies the entire chain of events necessary to reach that point (extractivism, colonialism, objectification of nature, etc.), not because we were ‘more technologically advanced’.

Yuk Hui reflects on this idea by attempting to answer the question, ‘Why did China and India, which were more technically “advanced” in the 16th century than Europe, failed to develop modern science and technology?’

His response is that the question itself is meaningless, because when we talk about being ‘more or less advanced,’ we think from the Western logic of universal technological progress, as if it were a race and we were all moving towards the same goal. He argues that Chinese history cannot be directly compared to Western history because they are based on different philosophies and ways of thinking.

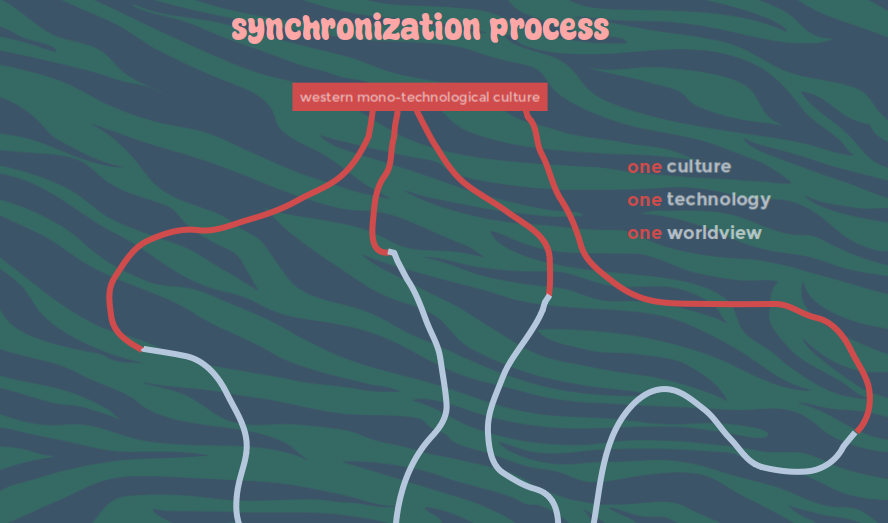

The dogma of technological progress masks a colonialist ideology that seeks to universalise capitalist thinking through technology and globalisation. To this end, different peoples and worldviews have historically been subjected to a synchronisation of techniques. In other words, diverse non-capitalist worldviews have been erased or replaced by a single universal way of thinking: Western mono-technological culture. We speak of ‘mono-technology’ because capitalist technology erases technical diversity and imposes itself as the inevitable development of an ‘advanced’ society, valuing only those techniques that are useful to capitalism.

In other words, this synchronisation has caused different historical temporalities to converge on a single temporal axis, prioritising specific forms of knowledge that fit the capitalist idea of what constitutes ‘advanced technology’.

In the monotechnological culture we currently endure, technology becomes the main productive force and largely determines the relationships between humans and non-humans, humans and the cosmos, nature and culture.

The desire of technology to be universalising and to become the foundation of everything implies a disconnection of techniques from reality, from worldviews, culture and territories, and it is this separation from reality that gives it its own apparently unstoppable autonomy.

This disconnection from reality means, as we have mentioned, that we do not have a worldview, a culture, or a moral code that acts as a boundary between what is possible and what is not possible. A radical approach requires us to establish our own boundaries that reflect how we want to inhabit this planet, which is necessary in order to re-imagine techniques within these boundaries and discard or combat those that fall outside them.

Yuk Hui understands technological globalisation as a form of neo-colonisation that imposes its rationality through instrumentality. In other words, using the tools of capitalism implies absorbing and adapting to the ideology that shaped it, so the use of technology must be part of a broader strategy of emancipating from it, carefully analysing the impact of its use and what ideologies we are integrating into the process.

In conclusion, the concept of cosmo-techniques aims above all to challenge the way in which technology has been understood during the 20th century, and he understands it as an exercise in decolonisation of different non-Western peoples.

Yuk Hui proposes a fragmentation of mono-technological culture to break with this imposed homogenisation and synchronisation, creating bifurcations towards diverse futures with different cosmo-techniques.

Permacomputing

Permacomputing draws inspiration from the philosophy of permaculture and applies it to computing, based on the premise of computing with limits. Some of its key ideas are:

- It focuses on computing resources: permacomputing displaces software as the centre or as an end in itself, and replaces it with a much broader concept: computing.

- By displacing software from the centre of the discourse, digitality is detached from the imaginary of computing.

- Software is inherently digital, so it depends on digital infrastructure.

- The practice of computing is historically much older than computer science. Digital computing is just one of many forms of computing. For example, an abacus or analogue computers are non-digital computing systems.

- Detaching digitality from the realm of computing opens up a range of possibilities that do not necessary depends on digital infrastructure or its continuity.

- Focuses on using already available computational resources, without producing more (e.g. maximising hardware lifespan and minimising energy use).

- Considers computing resources as a precious common good that must be managed collectively.

It is about using computing only when it has a strengthening effect on ecosystems.

- Attemps to provide the questions to design guidelines for post-capitalist computing with limits.

Three distinct approaches related to permacomputing can be distinguished:

- Frugal computing: treating computational resources as finite and precious, to be used only when necessary and as effectively as possible.

- Salvage computing: use only the computational resources already available, limited by what has already been produced. It advocates a drastic reduction in the use of artificial energy and relies on human ingenuity to turn problems into solutions, competition into cooperation, and waste into resources.

- Collapse computing: a post-collapse society that has eventually lost all its artificial computational capacity may still wish to continue the practice of computer science for various reasons. This approach has several key points:

- Re-use whatever has survived the collapse of industrial production or network infrastructure (but at the same time questioning if it has any collective benefit to do it).

- It prioritises community needs and seeks to contribute to collective knowledge in order to sustain computing practices in the face of infrastructure collapse.

- It is the practice of doing something with discarded items to transform waste into renewed resources.

Self-obviating systems

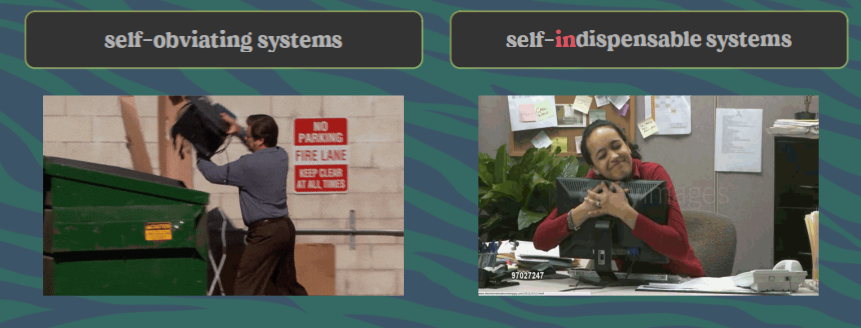

Permacomputing incorporates the concept of self-obviating systems, which means that:

- by design, the computer system should seek to make itself increasingly less necessary for the fulfilment of its purpose.

- and should gradually enable the autonomy and independence of individuals in relation to such systems.

Thus, we could say that we currently have the exact opposite: digital technology that makes itself indispensable, as it is designed to generate greater dependence on its use, thereby reducing people’s autonomy.

What is the role of Free Software?

The free software movement has a broad spectrum of ideological supporters, one of its best-known figures being Richard Stallman, a north-american liberal capitalist.

First of all, it is necessary to highlight the difference between ‘free software’ and ‘open source’:

- Free software is a social movement that defends users’ freedom to run, copy, distribute, study and modify software.

- All free software is also open source.

- Open source is a business model that highlights the commercial potential of sharing software source code and removes the philosophy and principles of free software to make it more attractive to businesses.

- Not all open source software is free software.

We dislike open source because it extracts the politics from the free software movement, but we also question the latter, the ideas on which it was created and its role in the fight against technocapitalism.

We are currently at a point where the commercial ideology of open source has devoured and diluted what could once have been the free software movement, although it is also important to consider that perhaps free software was never really intended to defeat technocapitalism, as it was conceived within its logic.

We find it strange to talk about open source or free software as if this label automatically made software more ethical, but:

- What is ethics under capitalism?

- How can we consider a software that needs digital infrastructure and extractivism to exist to be more ethical?

- Are we seeking a false notion of ethics within capitalism or are we seeking its destruction?

- Talking about ethical alternatives is a way of validating and strengthening the capitalist system, hindering any radically anti-capitalist proposals.

An example of this is open-source ‘Artificial Intelligence’, which is presented as an ethical alternative to more commercial ‘AI’ products, while omitting the fundamental problems of ‘AI’ or its dependence on digital infrastructure under the justification that ‘it can be run locally’, which also requires ignoring the fact that what is run locally are the parameters of an already trained model. In other words, there are really no arguments to justify how ‘AI’ acquires a higher degree of ‘ethics’ just because it is labelled as open source, which, moreover, is not even true. Along the same lines, we detect the same problem in discourses that talk about ‘ethical uses of AI’ or ‘feminist AI’, etc.

Free Software is not anti-capitalist

The main concept on which the philosophy of free software is based is: freedom.

However, ‘freedom’ is a very ambiguous term, which can have different nuances with totally different implications. In this case, the freedom of north-american Richard Stallman, the best-known promoter of free software, is the individual freedom of the user, that is, the type of freedom that liberals understand as the ultimate expression of fair competition in the free market.

Free software allows users to own a copy of software and do whatever they want with it. Instead of challenging the intellectual property system, free software licences use this same regulatory system to ensure the user’s individual freedom.

It is true that, in part, this legal framework can offer institutional mechanisms to ensure that its principles are complied (theoretically), but the historical process that led to this outcome also contained other more critical paths that rejected the validation of legal intellectual property systems and advocated, instead, their destruction. What won out was a more liberal vision. However, from a radical point of view, free software was unlikely to become a disruptive political movement since, as we mentioned earlier, it was conceived within capitalist logic and can coexist perfectly integrated into this system.

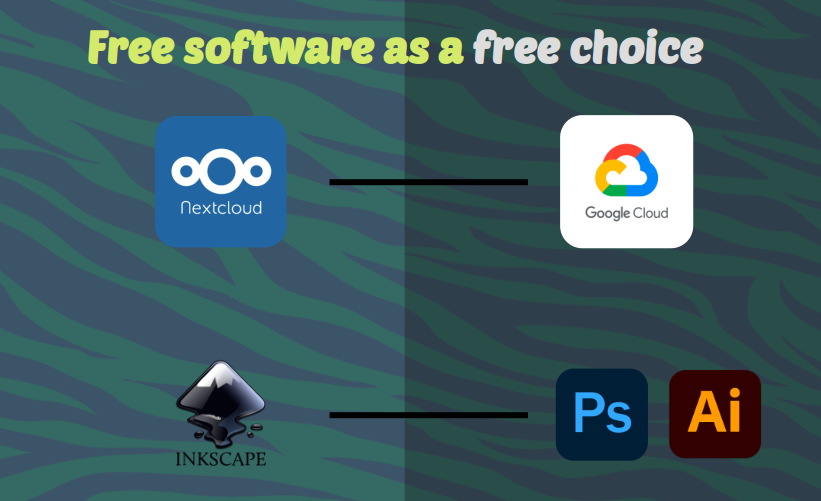

Free software as a choice

Free software movement has the risk of presenting software as a free choice under capitalism, as an ethical choice within the system.

Given all the software options available, we have the option of choosing free software alternatives. For example, instead of using Google Cloud, we can use Nextcloud, or instead of Adobe suit (Photoshop, Illustrator, etc.), we can use Inkscape.

But, some questions arise:

- Why do we want an alternative to a capitalist need?

- How could be ethical to use Inkscape instead of Adobe if we are only questioning a very small fraction of the problem?

- Why are we validating the underlying premises that justify the development of a software?

- Do we even need another app for this?

- Are we simply running the same race of progress that the system has placed us in? Perhaps we need to stop running and think about where we really want to go.

This dynamic of choosing apparently more ethical choices is exactly the same when we buy ‘vegan’ cheese instead of ‘non-vegan’ at the supermarket, or buying “organic” oatmeal cookies instead of the ‘non-organic’ ones, and thinking that by choosing a different product we are somehow questioning or fighting the capitalist production system or any of its ideology. Well, definitely individual choices are no threat and neither it is using the same underlying infraestructure.

There is no ethic product under capitalism and no product will end it or end speciesism, colonialism, and anthropocentrism, because capitalism would not permit, finance, or sell anything that could truly destroy it.

Free software as an end

Free software, established as a free choice under capitalism, becomes an end in itself, without any real goal of overthrowing the capitalist system. In this way, we fall into the trap of believing that if all software we use is free software, then we are fighting capitalism or living in a “more ethical” way.

After all, the fact that free software has become an end in itself explains why there is so little criticism, in general, of the digital infrastructure within the movement. Capitalist technology, in fact, becomes necessary to maintain the technological infrastructure that enables software development and sustains this digitised life.

We need free software to be a means, not an end.

Free software as a means

Free software can only have a radical potential if it is repositioned as a means and subjected to a much greater objective: the destruction of capitalism and an end to extractivism.

Free software that simply seeks to keep pace with current technological developments or offer alternatives to proprietary software is absolutely zero disruptive.

Free software may act as a medium when:

- It helps reduce dependence on digital technology and, therefore, on its infrastructure.

- Fights against the expansion of digitalisation

- It gives us back some of the autonomy we have lost on commercial platforms (let’s migrate to the fediverse).

- Seeks to be compatible with older devices, considered obsolete due to a lack of compatible software.

Ultimately, free software must be able to betray itself in order to put an end to the capitalist digitalisation project that gave it birth.

We could consider permacomputing to be the broader perspective that the free software needs, as it reorganises priorities, decentralises software from the centre of the movement, and sets out a path forward that radically challenges progress and capitalist infrastructure.

References

- Book Técnica y tecnología, Adrián Almazán

- Book Technocapitalism: a critical prerspective on technological innovation and corporatism, Luis Suarez-Villa

- Article What is technoscience?: technoscience, power and environment, Alonso Nava

- Book Fragmentar el futuro: ensayos sobre tecnodiversidad, Yuk Hui

- Neil Postman’s talk 6 questions about new technologies (1998)

- Tecnocapitalismo de libre-ta

- Richard Stallman saying that free software is not against capitalism: Interview with Richard Stallman (2004)

- Website permacomputing wiki

- Article Permacomputing: a holistic approach to computing and sustainability inspired from permaculture, Devine Lu Linvega